The energy was contagious. Everyone was friendly, open and eager to introduce themselves or share their work. The Bridges MathArt Conference had an unbelievably welcoming community, making it feel like a joyful reunion where many attendees reconnected with familiar faces. After more than 20 years, the conference has grown into a genuine, thriving community.

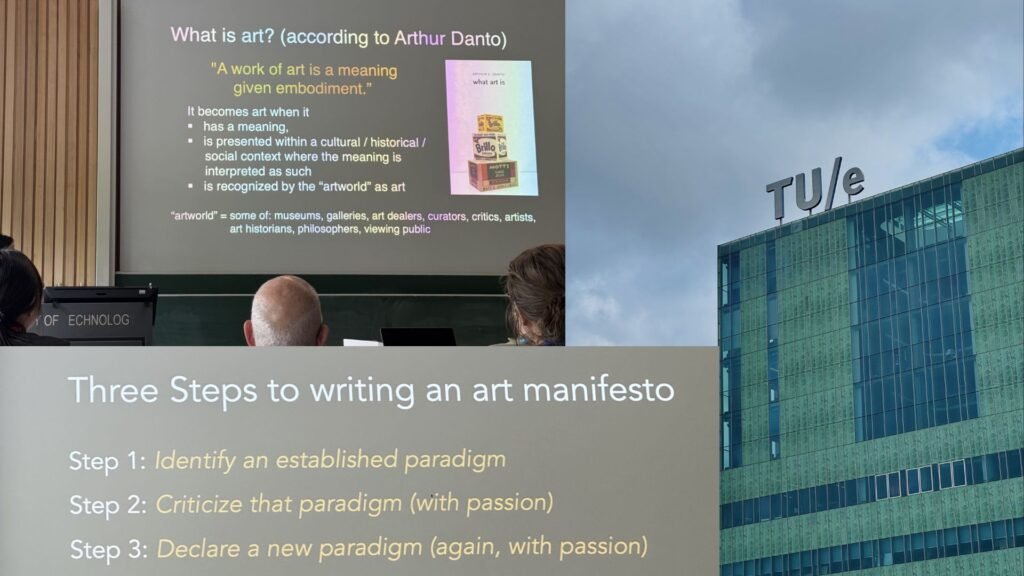

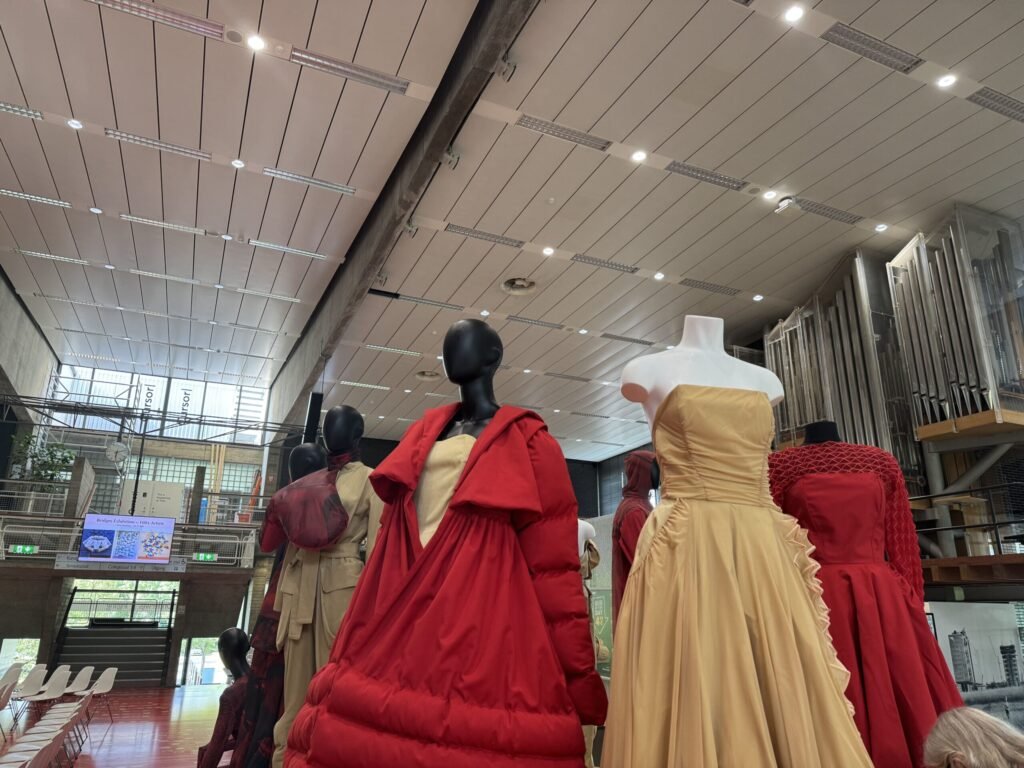

Organized by The Bridges Organization, the annual Bridges MathArt Conference has been held since 1998 across North America, Europe, and Asia, celebrating the connections between mathematics, art, culture, music and architecture. Featuring everything from live organ performances and geometric constructions to math-inspired fashion and thought-provoking talks, this year’s conference took place from July 14th–18th at Eindhoven University of Technology in the Netherlands. Unsurprisingly, in the process of bridging mathematics and artistry, this convening also lent itself to several insightful conversations about art-science and the importance of interdisciplinarity.

The integration and exchange of disciplines are increasingly essential in today’s world, where many of the challenges we face—such as environmental issues, technological ethics and global disparities—are complex, interconnected and resistant to isolated solutions.

The Dilemma of Categorization

Tuesday’s plenary speaker, British mathematician, writer and artist Edmund Harriss, spoke about how we navigate identity, knowledge and creativity across disciplines. He began by distinguishing sincerity and authenticity, two concepts often blurred but fundamentally different. Sincerity is about aligning oneself with a given social role, shaped by cultural expectations. Authenticity, on the other hand, is the inverse: reshaping one’s role to align with the self. This distinction framed a deeper discussion about the nature of interdisciplinary work. Disciplines, the speaker argued, don’t just differ from one another; they create tension at their boundaries. Therefore, interdisciplinary work doesn’t simply fill gaps; it highlights the arbitrary nature of those gaps. The relationship between disciplines, like math and art, exemplifies this: math leans toward sincerity, structured and rule-bound, while art leans toward authenticity, expressive and fluid.

Another speaker, Professor and multi-media artist, Fumiko Futamura, delivered a workshop that included a highly engaging and intellectual discussion on the value of a manifesto in math art spaces. Fascinating questions were raised about how we classify math art, whether it leans more toward being a subcategory of art or science. What qualifies as math art, and what doesn’t? The discussion concluded with a general consensus that creating a math art manifesto may not be easy, given the diverse interpretations of what math art is and who it’s for.

Harriss explored the idea of working ‘as if’—approaching science not because it reveals absolute truth, but by acting as if it can reveal a truth. Likewise, math-art is mathematics performed as if it were art, an act that invites reflection not just on aesthetic value, but on how we navigate between sincerity and authenticity. It challenges us to consider when we are following inherited roles and expectations, and when we are reshaping them in alignment with our creative instincts. In this way, interdisciplinary work doesn’t just blend disciplines; it exposes the tensions and possibilities between them.

The limitations that labels can impose and how they influence the way people share their work came up repeatedly throughout the conference. During a plenary discussion, one audience member asked, “How can we get the artists to accept us [i.e., math artists]?” However, art-science isn’t about seeking validation from established disciplines or waiting for them to make space for innovation. It’s up to interdisciplinary thinkers to recognize the value of something entirely new, and to push it forward with full confidence, in pursuit of what has yet to be imagined.

“Art-science isn’t about seeking validation from established disciplines or waiting for them to make space for innovation. It’s up to interdisciplinary thinkers to recognize the value of something entirely new, and to push it forward with full confidence, in pursuit of what has yet to be imagined.”

A Third Space

Futamura’s open discussion prompted the idea that art-science combinations, such as math art, nanoart, bioart, neuroart, and others, may need to be classified as something entirely new, rather than as subcategories of their respective art and science domains. Art-science creates a third space because it addresses a different need, separate from the pure value of science and the pure value of art, both of which remain valid in their own right and should not be replaced.

Edmund Harriss’s talk drew from both category theory and Taoist philosophy to show that disciplines shouldn’t just be “added together” like ingredients in a recipe. In line with the Taoist idea that foundations shift the moment you define them, interdisciplinary practice is inherently unstable—but also fertile.

We agree that embracing art-science as its own category opens up new possibilities without imposing restrictions on the field or discipline in question. What happens when a mathematician with an interest in biology uses visual art to highlight mathematical forms in nature? Trying to label that person strictly as a mathematician, biologist or artist becomes limiting. Art-science opens up space for curiosity, impossibility, and creativity within and beyond scientific research, rather than dividing it.

The Crearte Foundation for Art-Science Innovation is committed to forging a path where this new category can not only exist but exist sustainably. We aim to support the development of art-science practices and drive impact, discovery, creativity and change, especially in the lives that need it most. Art-scientists must cultivate a confidence in their work that frees them from apologizing for their interests. Instead, they should see their work as a direct response to the growing need for interdisciplinarity in our world.

Lasting Impressions: Let’s Build Relationships

What will stay with us from our time at Bridges?

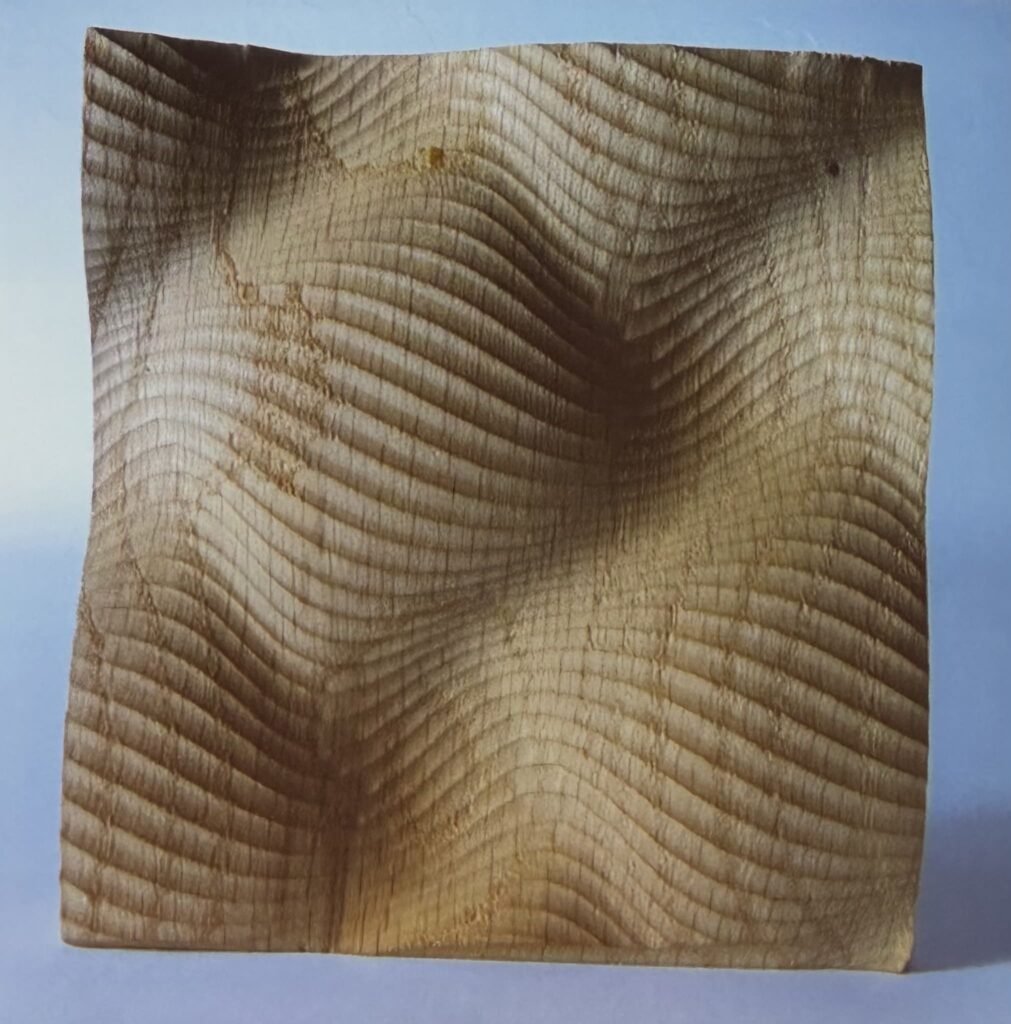

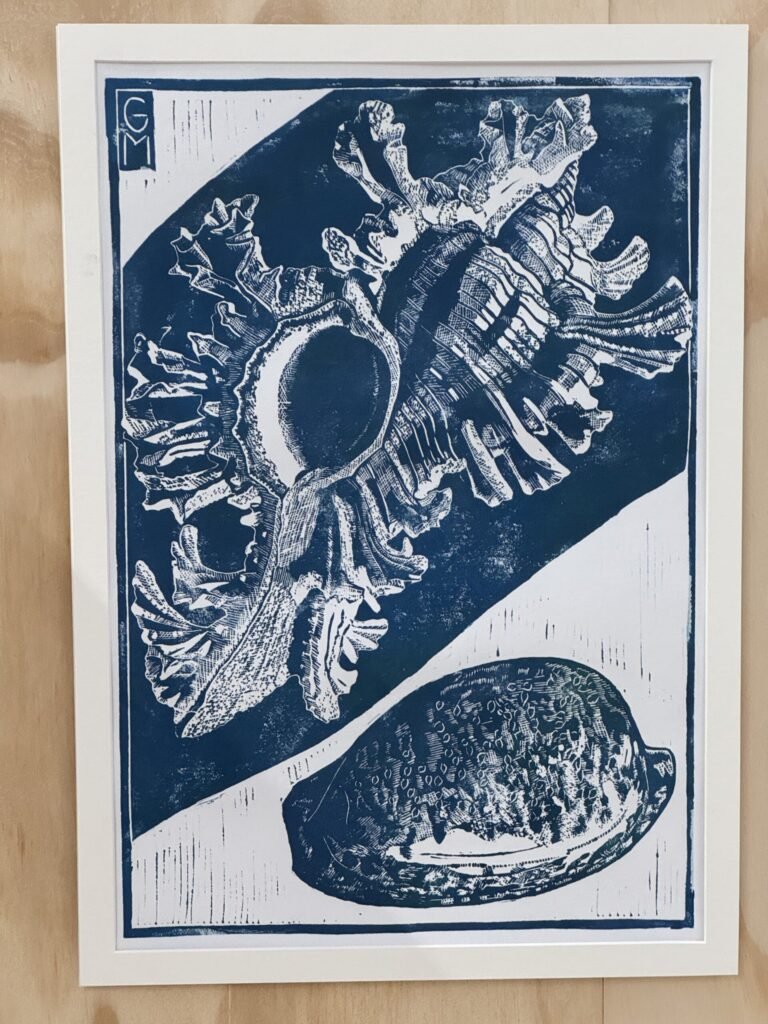

First, the atmosphere—a rare blend of intellectual generosity, playfulness and deep curiosity. From the resonant notes of live organ playing to a fashion show inspired by mathematical forms, from hands-on workshops to gallery conversations that spilled out of the campus halls and into the streets of Eindhoven, the conference was alive with creativity. It was a space where ideas moved freely, and where people from many backgrounds came together not just to present, but to experiment, connect and be inspired.

In the same breath, we saw a growing call for greater institutional support and recognition of art-science practices. While the Bridges MathArt Exhibition featured breathtaking works, many math-artists faced external barriers such as limited funding, minimal institutional backing and challenges producing their research-creations. These gaps reflect a broader lack of infrastructure for interdisciplinary work in general.

Secondly, it became increasingly clear, through the leading example of the Bridges Organization’s conference, that support for art-science must also include space for experimentation and responsiveness. Harriss concluded his talk by advocating for curiosity-driven manufacturing, encouraging math artists (or art-scientists) to create not only what is functional or beautiful, but what meaningfully addresses real human needs. As we face complex challenges demanding transformation in our knowledge systems, Harriss poses a crucial question for all of us: How do we move from what currently exists to what people truly need, without losing sight of beauty, utility and wonder?

How do we move from what currently exists to what people truly need, without losing sight of beauty, utility and wonder?

We leave with a call for a shift in perspective. Rather than building self-contained worlds, interdisciplinary artists should focus on building relationships—relationships between ideas, fields and people. Bridges sits within the broader landscape of art-science, alongside many other interdisciplinary combinations, and its relationship with them is part of the ongoing art-science dialogue.

All in all, Bridges offered an alternative to typical academic conferences, embracing a more open and creative approach rather than focusing solely on traditional definitions of doing research ‘correctly.’ There’s a time and place for that, of course—but the lighthearted, exploratory, curiosity-driven atmosphere at Bridges was truly refreshing. The Crearte Foundation looks forward to becoming a regular part of the Bridges MathArt community.

Gallery

Thank you to Hotel The Match Eindhoven for graciously accommodating our stay during the conference. Your hospitality made our experience even more enjoyable.