When Beauty first arrived at the castle, she was repelled by the Beast. But over time, through experiences and emotional connection, what once seemed monstrous became beautiful. What she saw and heard reshaped how she felt, and what she felt changed what she understood. Her perception of him shifted, reminding us that beauty is not simply observed, but constructed in the brain.

In many ways, the same is true when we experience art.

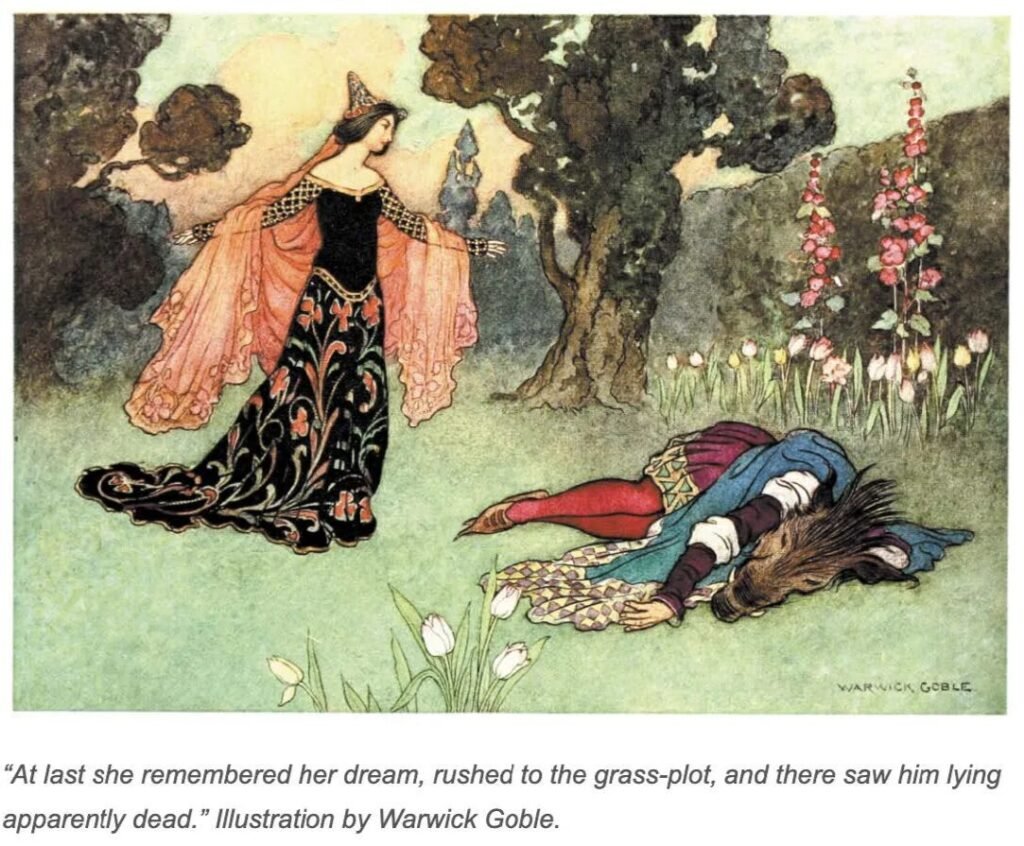

Have you ever stood in front of a painting, watched a dance performance, or listened to a song, and felt something you couldn’t quite explain? Why is it that one piece can move us more than another? Take, for instance, this illustration by Warwick Globe of Beauty and the Beast. How does it make you feel? Maybe you’re drawn to its romantic style because you’re a painter yourself. Maybe it’s your favourite fairytale. Or maybe it doesn’t move you at all.

The English art critic Clive Bell once wrote, ‘If you can tell me everything that aesthetic experiences have in common, you will have answered the question of aesthetics.’ However, for a long time, the abstract study of beauty only belonged to philosophers and art historians. While Plato believed beauty was tied to perfection and truth, Aristotle saw beauty as order, harmony and purpose.

But what if the answer isn’t just philosophical, but also biological? Enter neuroaesthetics, a field at the intersection of neuroscience and art, bridging two fields that have for a long time been separated in education, research, and conversations.

What is Neuroaesthetics?

The term “neuroaesthetics” appeared in the last decade of the 20th century to describe an emerging discipline in cognitive neuroscience that aims to uncover the science behind aesthetic experiences. Rather than asking what beauty is, neuroaesthetics asks what happens in the brain when we experience beauty and artistic expression, and how our cultural backgrounds, memories, emotions, and personal preferences influence what we find moving–or not.

To respond to these questions, scientists are looking at how we perceive, process and respond to various art forms, including but not limited to, visual arts, music and literature.

Mapping Aesthetic Response: fMRI and the Beauty Spot

The brain is often treated as a cold and calculating machine, when in reality it is composed of complex intuitive and emotional networks that operate independently and collectively.

It’s no surprise that neuroaesthetics gained momentum around the time when innovative technologies like functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI) and EEG made it possible to observe the brain in real time. While philosophers and art historians hadn’t previously seen a connection between aesthetic experiences, images of cerebral activity allowed scientists to begin mapping neural responses to different stimuli.

Dr. Semir Zeki, a Professor of Neuroaesthetics at University College London, identified a specific area of the brain called the medial orbital frontal cortex, which consistently lights up when people experience beauty, regardless of the source. Stronger activity in this region is observed when something is perceived as more beautiful.

Despite this shared neural response, scientists emphasize that aesthetic experiences come from dynamic interactions between multiple regions of the brain, shaped by personal, emotional, and contextual factors.

The Aesthetic Triad: How the Brain Builds Beauty

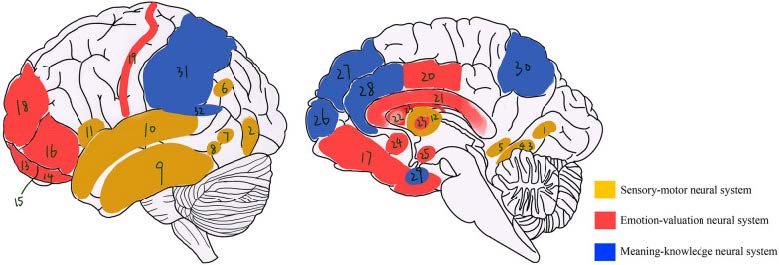

Picture Beauty watching the Beast not just with her eyes, but through a complex interplay of sensory input, emotion and memory. Enter the “aesthetic triad”, an intuitive model introduced by Anjan Chatterjee and Oshin Vartanian (2014) that describes how three core systems of the brain interact to receive and actively interpret art.

● The sensory–motor system (occipital and parietal regions) processes sensory input.

● The emotion–valuation system (amygdala, insula, and orbitofrontal cortex) generates emotional responses and assigns value, such as pleasure or discomfort.

● The meaning-knowledge system (prefrontal cortex, default mode network, and temporal lobe) introduces memory, culture, and understanding.

Li, Rui, et al. “Figure 2: Brain Regions from Three Neural Systems.” Review of Computational Neuroaesthetics: Bridging the Gap between Neuroaesthetics and Computer Science, Brain Informatics, vol. 7, no. 1, 2020, p. 16. PMC, doi:10.1186/s40708-020-00118-w.

For Beauty, the sensory-motor system might take in the Beast’s unusual features and rough voice. The emotion-valuation system might register fear, curiosity or compassion. And her meaning-knowledge system draws on her past and the values that slowly reshape her judgment.

Mirror Neurons

One way to understand this is through an example. When you watch a ballet performance, you may feel a sense of movement and emotion yourself. This happens because your brain’s mirror neurons are simulating the actions and emotions you observe. Interestingly, studies have found that familiarity enhances this effect. Ballet dancers, for instance, are likely to show stronger mirror neuron activation when watching a dance performance.

This phenomenon is part of what neuroscientists call the mirror neuron system, a recent discovery that sheds light on how our brains both create and appreciate art. First identified in monkeys by Gallese and Colleagues (1996), and later also found in humans, mirror neurons are a group of brain cells located in the posterior parietal cortex with connections to the premotor cortex. This reciprocal connection may support embodied cognition, allowing us to internally simulate perceived actions and emotions, enhancing our capacity to connect, empathize and learn through imitation.

Importantly, mirror neurons may also inform how we create art. Just as we internally simulate the actions and emotions we observe, artists, musicians and performers draw from their own embodied experiences to express emotion and movement through their works.

Aesthetic Judgments and Preferences

Beauty’s growing affection wasn’t about the Beast changing, but about her own emotional experiences, growing familiarity with him and evolving values reshaping what she perceived as beautiful. In the end, beauty isn’t objective and universal, it’s shaped by who we are.

According to Brattico & Pearce (2013), aesthetic preferences are shaped by familiarity with the art form, cultural background, emotional responses, expectations and appraisal biases. For example, someone who regularly practices the piano is more likely to enjoy Beethoven’s music than someone without that experience. Studies have also shown that factors such as symmetry, colour and composition influence aesthetic judgments, as human brains tend to prefer order and predictability (Jacobsen et al., 2006).

Artists, Neuroscientists or Art-Neuroscientists?

Neuroaesthetics has clearly taken off in the scientific community, but what if, as science studies art, art is also studying science?

Galleries like Tate Britain are exploring the artistic potential of scientific research through the merging of art and technology. Namely, the 2015 exhibit Tate Sensorium combined the exploration of our 5 senses–visual, taste, smell, sound and haptic sensations with the use of perspiration-detecting wristbands to measure public engagement. Similarly, Olafur Eliasson’s immersive installation Room for One Colour (2003) uses colour and light to stage human vision as the subject of the artwork itself, bringing nonconscious dimensions of visual cognition into conscious awareness.

Although neuroaesthetics is more often discussed in scientific circles, it is also gaining traction in the art world, with artists exploring common scientific questions. Perhaps innovation lies not in dividing art and science, but in fusing them. As artists learn from neural maps and scientists learn from artistic intuition, barriers are becoming increasingly blurred, creating room for collaboration.

A Tale of Two Worlds

Just like Beauty learned to see the Beast differently, not because he changed but because her perception of him did, neuroaesthetics suggests that beauty isn’t a fixed trait but an evolving dialogue between sensation, memory, culture, and emotion. The brain doesn’t simply receive beauty, it builds it. Today, our understanding of aesthetic experiences goes beyond the abstract ideas of Plato and Aristotle, opening a new space for interdisciplinary exploration and innovation. After all, maybe Beauty and the Beast is trying to tell us that beauty is not only in the Beast, but also in the one who learns to see it.